Mahatma’s agonies

The Muslim League ministry in Bengal should be able to control the outbreak of disorders in East Bengal, said Mahatma Gandhi on 21 October 1946 in an interview to Preston Grover of Associated Press of America.

For his personal political ambitions, thousands were butchered in the streets of Calcutta and after the formation of Pakistan, Jinnah, at his hypocritical best, talked about secularism and a liberal democratic state. Was this man liberal?

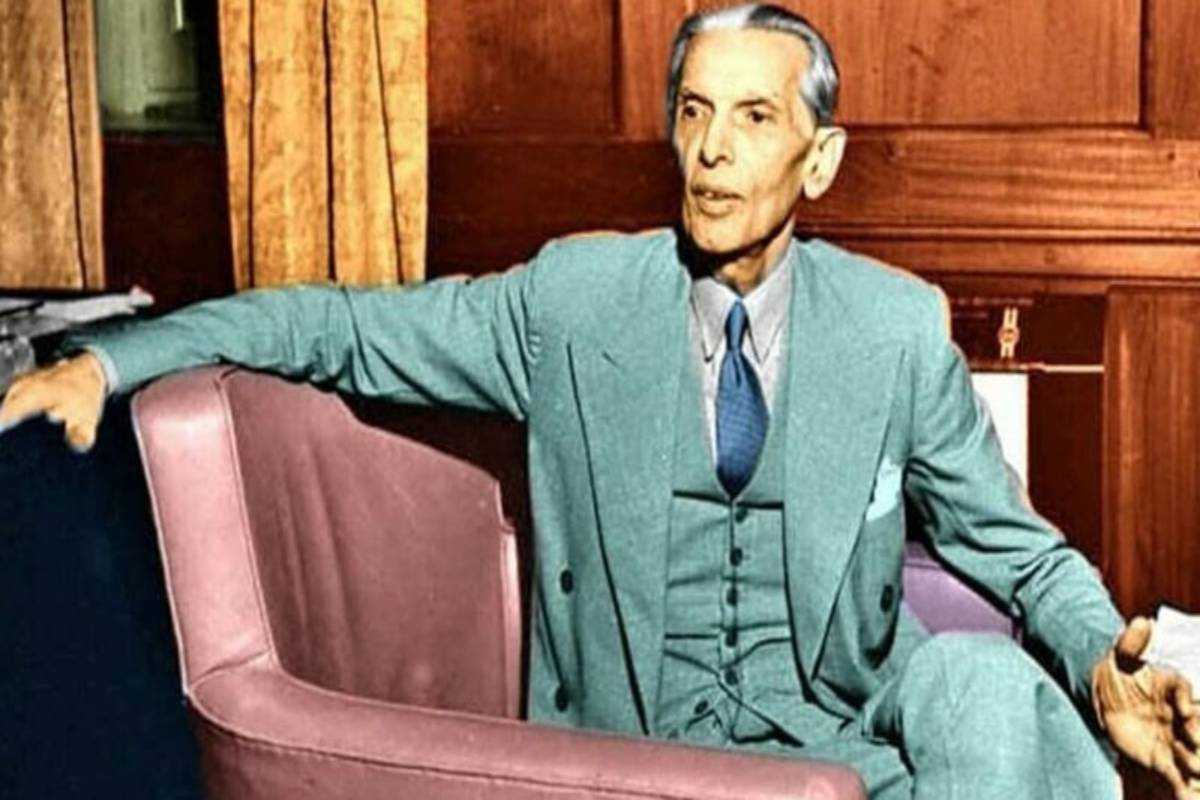

Mohammed Ali Jinnah

The Partition narrative is riddled with unanswered questions and interpolation of myths. The myths were deliberately constructed to explain away misdeeds of leaders by presenting counterfactuals. One such myth is Jinnah’s liberalism.

Before Partition, there were two different strands of Muslim identity politics. One was related to Pan-Islam and the other to separate statehood. The Khilafat movement brought in issues of Pan-Islam by clamouring for the restoration of the Caliphate in Turkey. Gandhi lent support to it, despite its regressive nature, to put an end to Muslim passivity in the freedom movements. Ironically, Muslims hailed the move and participated in anti-British agitations mainly because they were happy with the assertion of their exclusive identity. The moment the non-cooperation movement, which was launched on the twin issue of Punjab wrongs and Khilafat, was called off the bonhomie with Muslim participation was lost.

We were frequently told by scholars that Jinnah had always been the staunchest critic of Khilafat. He always condemned it as anti-modern and tried to stop movements for a Caliphate in Turkey. This is factually incorrect. Jinnah was the first leader of an all-India stature to have warned the British of the consequences of reducing the status of the Khalifa. He repeated this warning in September 1919 to Prime Minister Lloyd George cautioning him of the possible impact of such a step on Muslims in India.

In January 1920, he was part of the Khilafat delegation that waited upon Viceroy Lord Chelmsford. In March, the Khilafat Conference sent a delegation to meet the Prime Minister in England but it failed to elicit any positive response. A crestfallen Jinnah, witnessing Gandhi’s growing popularity among the Muslims through Khilafat agitations, desperately tried to dissuade Gandhi and the Congress from raising the Khilafat issue. His so-called role of a moderniser was, therefore, shaped by his personal political ambitions and not by any objective of advancement of Muslims in India.

Jinnah failed to become the sole spokesperson of Muslims on both counts ~ pursuing the Khilafat demands and stopping Gandhi’s Khilafat agitations. Nevertheless, he did not have to wait for long to have his own chance. When the Non-Cooperation movement was called off unceremoniously after the Chauri Chaura incident, the Muslims were left in the lurch and the Khilafat movement lost all its relevance after the Turks abandoned Caliphate. The ground was ready to harvest.

Seeds of separate nationhood had already been sown by the great educationist and moderniser Syed Ahmed Khan in his reformation movement. It greatly influenced the Muslim Salariat. Salariat is a salaried class of people appointed to the posts of bureaucrats or high officials. Muslim Salariat was much less in position and posts in the state apparatus compared to their Hindu counterparts. These people were aggrieved. Long before the rise of Jinnah, Syed Ahmed Khan propagated the two-nation perspective. He said, “Now suppose the British are not in India and that one of the nations of India has conquered the other, whether the Hindus the Mohammedans or the Mohammedans the Hindus. At once, some other nation of Europe … will attack India.’’ The Salariat sentiment informed by Syed Ahmed’s two nation perspective, substantially contributed to Muslim League’s fanatic adherence to the Pakistan demand. But it does not explain why the entire Muslim community rallied round it leaving ideas of Pan-Islam.

Some scholars have argued that Hindu domination of Congress and rise of the Hindu Mahasabha forced the Muslim League to pursue the agenda of separate nationhood. Again, this is, in no way, corroborated by facts. In the elections to the legislative assemblies in 1937, the Hindu Mahasabha did not win a single seat. Muslim League also failed to enlist the support of the majority in most of the provinces except Bengal and Sind. Even in the Muslim majority NWFP, they could not make any headway.

One year after, repeatedly facing Muslim League’s electoral defeats, Jinnah adopted a strategy of indicting Congress as a communal organisation. It was unfolded in the report of the Pirpur Enquiry Committee appointed by All India Muslim League (November 1938). The Committee was tasked to inquire into Muslim grievances in Congress provinces. The report said that Congress had an implicit tendency of stopping cow slaughter and it fomented animosity towards the Muslims as the hostile ‘other’.

The British government rubbished it. Nevertheless, this campaign of falsehood is significant as it laid bare the political objective of Jinnah. He wanted to project himself and the Muslim League as the sole representatives of the Muslims in India by projecting an exclusive Muslim identity.

The diabolical process of campaigns that followed culminated in the call for ‘Direct Action’. On 29 July 1946, Jinnah and his working Committee of the Muslim League presented two resolutions. The second resolution said, “… the time has come for the Muslim Nation to resort to Direct Action to achieve Pakistan to assert their just rights …’’ . After the resolution was passed Jinnah concluded: “… To-day we have said good-bye to constitutions and constitutional methods.’’ A correspondent of Daily Telegraph asked Jinnah what he meant by “Direct Action’’? Jinnah replied, “there would be mass illegal movement.’’ Later, when the correspondent showed him the article before cabling it home Jinnah changed illegal to “unconstitutional’’. Whatever might have been the official statement, the incidents of 16 August 1946 bear testimony to his dark intentions.

The entire city of Calcutta turned into a veritable slaughter house. Stench of decomposed bodies was everywhere. Piles of dead bodies on handcarts were left abandoned and as recorded by General Francis Taker (in charge of India’s eastern command), “Once it was known that the… Englishmen were collecting the dead, more bodies appeared from the labyrinth of houses and hovels’’. The mastermind of ‘Direct Action’, purely for the ambition of putting himself and Muslim League at the centre stage of politics, remained unmoved by these ghastly acts.

When he was asked about the Great Calcutta killings by a foreign news agency, he said, “If Congress regimes are going to suppress and persecute the Mussalmans, it will be very difficult to control disturbances.’’

No remorse, no heart burning, only cold calculations for a move towards division. Here, I cannot resist the temptation of citing an instance of his covert design of inciting fanaticism. On 24 August 1946, Wavell announced the formation of a new interim government by Nehru and thirteen colleagues of his choice which included non-League Muslims. Two days after Wavell’s broadcast, Jinnah, condemning the Viceroy’s announcement, said, “… the step he has taken …is fraught with dangerous and serious consequences… he has added insult to injury by nominating three Muslims who, he knows, do not command either the respect or confidence of Muslim India.’’

A week after Wavell’s announcement, Sir Safaat Ahmed Khan, one of three non-League Muslims named to Nehru’s cabinet was stabbed seven times by two young Muslim League fanatics. If this is viewed as a mere coincidence, I would say, this was too much of a coincidence. For his personal political ambitions, thousands were butchered in the streets of Calcutta and after the formation of Pakistan, Jinnah, at his hypocritical best, talked about secularism and a liberal democratic state. Was this man liberal? One wonders.

Advertisement